WRITTEN BY: Daniel J. Patterson

Article at a Glance

Seed oil consumption is on the rise in the last 100 years, paralleling the increase in obesity rates.

Seed oils are high in omega-6 linoleic acid, which is a precursor to endocannabinoids like AEA and 2-AG. These compounds appear to stimulate appetite, contribute to weight gain, and cause the "munchies."

Endocannabinoids are naturally occurring compounds in our bodies, and similar to the active ingredients in cannabis, they play a vital role in regulating appetite and hunger signals.

CB1 receptors, which are part of the endocannabinoid system, play a crucial role in weight management, as demonstrated by studies on Rimonabant, gastric bypass surgery, and genetically modified mice.

Increased AEA (endocannabinoid) levels, resulting from higher linoleic acid consumption, can counteract the positive effects of gastric bypass surgery on fat loss and metabolism, emphasizing the significance of CB1 and AEA in the development of obesity.

The good news is that understanding the link between linoleic acid and obesity offers a promising solution. By consuming less linoleic acid, you may be less likely to experience the munchies or increased appetite, making it easier to maintain a healthy weight.

Introduction

The “munchies,” an infamous side effect of cannabis use, is characterized by increased hunger and a seemingly endless urge to snack. Interestingly, research has found a connection between this phenomenon and the consumption of seed oils.

Seed oils, a subcategory of vegetable oils, are extracted from the seeds of crops and include soybean oil, sunflower oil, corn oil, cottonseed oil, grapeseed oil, and more. These oils are incredibly common in packaged foods and can be found in most restaurant meals, from fast food to fine dining.

Due to their high content of a type of polyunsaturated omega-6 fat called linoleic acid, seed oils have been linked to a laundry list of chronic health issues like inflammation, diabetes, heart disease, and more [*,*,*,*,*,*,*,*].

While humans evolved to consume low levels of omega-6 fats in their diets, the widespread adoption of seed oils during the 20th century led to a 10-fold increase in the average dietary intake of these fats [*,*]. Meanwhile, obesity rates have increased dramatically over the same time period, with over 40% of adults in the U.S. now being classified as obese [*].

In this article, we will dive into the relationship between seed oils and the munchies, investigating the possibility that the widespread consumption of seed oils may be contributing to increased appetite and unwanted weight gain.

The Science Behind The Munchies

The munchies may be a colloquial term, but the intense hunger that many people experience after using cannabis is not merely anecdotal. While cannabis is a plant containing a variety of compounds, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the primary cannabinoid responsible for the psychoactive or "high" sensation and increased appetite.

Many studies have confirmed a direct link between THC use and increased appetite [*,*,*,*]. In fact, THC is an FDA-approved prescription drug used to stimulate appetite, particularly in patients who struggle with conditions like chronic or chemotherapy-induced nausea [*,*].

THC works because humans and other animals with spinal cords have receptors in their brains (and throughout the body) called CB1 receptors. These work with THC molecules like a lock and key – the THC fits into the receptor and activates it, stimulating side effects like hunger.

However, THC isn’t the only compound capable of activating CB1 receptors. Your body naturally produces compounds called "endocannabinoids" ("endo" meaning internal or within).

These endocannabinoids, primarily 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA), can also activate CB1 receptors and trigger hunger – even on a full stomach.

As it turns out, the production of these endocannabinoids is closely tied to the types of fat you consume. For instance, your body makes 2-AG and AEA endocannabinoids exclusively from arachidonic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid) [*]. And while arachidonic acid is present in trace amounts in food, your body primarily produces it from its precursor: linoleic acid [*].

In other words, when you consume linoleic acid (typically from seed oils), some of it is converted into arachidonic acid, which leads to the production of endocannabinoids 2-AG and AEA. These endocannabinoids stimulate our appetite and ultimately, may cause you to eat more.

Linoleic Acid and Weight Gain

There are a lot of theories about the dramatic rise in obesity during the 20th century (and its continued rise to this day). But one cause has gone under the radar for decades: the rise in seed oil consumption.

Seed oils (packed with inflammatory omega-6 linoleic acid) are in almost every processed, packaged food and in most restaurant food. So it’s no wonder that the average person today is eating 10 to 20 times more omega-6 linoleic acid than in previous generations [*,*,*,*]. As a result, the modern diet is characterized by a high omega-6 to omega-3 ratio, which may contribute to the excessive production of AEA and 2-AG [*].

The excessive production of AEA and 2-AG appears to overstimulate CB1 receptors, leading to increased weight gain and metabolic dysregulation [*]. In fact, numerous studies have found that people with obesity tend to have higher circulating blood levels of 2-AG and AEA compared to those who are lean [*,*,*,*,*,*].

Because the endocannabinoid system is found in all mammals, research on rodents can provide insights into how linoleic acid affects 2-AG, AEA, and obesity in humans.

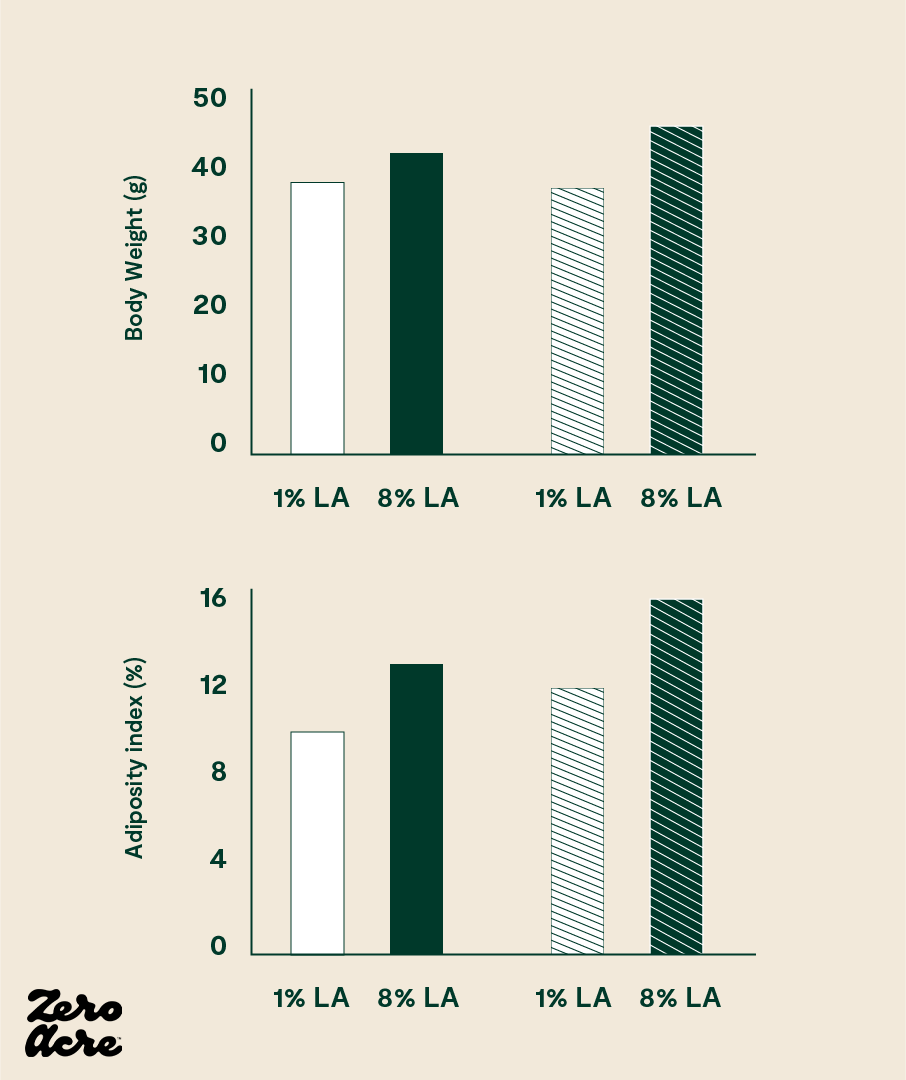

In a 2012 study, researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) divided mice into different groups and fed them high-fat chow with varying levels of linoleic acid [*]. One group was fed chow with 8% of its calories as linoleic acid, while the other group was fed chow with only 1% of calories as linoleic acid.

The only difference between the two groups was the amount of linoleic acid in the chow they were fed — everything else in the diets of the two groups remained the same. The researchers also provided the mice with unrestricted access (24/7) to their food in order to mirror the eating habits of humans in developed countries.

The study found that the mice consuming a higher percentage of linoleic acid gained significantly more weight than their counterparts on the lower linoleic acid diet. The mice consuming the higher linoleic diet had elevated levels of 2-AG and AEA, consumed 18% more calories, and weighed 20% more [*].

The researchers designed the study to mirror the 20th-century shift in Western countries, where linoleic acid intake increased from 1% of calories to 8%, a change that has closely correlated with rising obesity rates.

The chart above shows the results of a mice study comparing medium-fat diets (open bars) to high-fat diets (striped bars).

Subsequent studies replicated their findings in more mice and even in salmon [*,*]. Most strikingly, when mice were fed a diet containing salmon raised on a high-linoleic acid diet, they gained more weight than mice fed a diet containing salmon raised on a lower-linoleic acid diet.

Although several studies have shown that linoleic acid from vegetable oils can have obesogenic effects, it wasn't until the 2012 study by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that linoleic acid was isolated as a dietary variable, demonstrating a direct link between elevated levels of dietary linoleic acid, increased levels of 2-AG and AEA, and weight gain in mammals [*,*,*,*,*,*].

According to these studies, linoleic acid intake leads to dose-dependent increases in body weight, body fat percentage, feed efficiency, and food intake in mice. And similar effects may be present in humans [*].

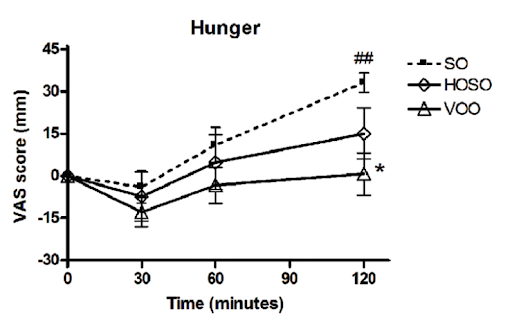

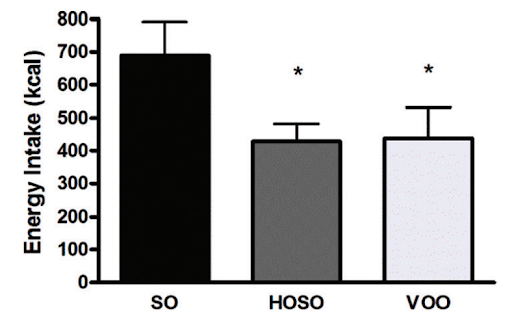

The endocannabinoids 2-AG and AEA essentially function as hunger-regulating hormones that increase when you haven't eaten and decrease after you've consumed food [*]. Conversely, oleoylethanolamine (OEA) exhibits the opposite pattern, decreasing when you're hungry and increasing after eating [*].

In one human study, participants who consumed a meal with high-linoleic-acid soybean oil reported consuming more calories and feeling less full compared to those who consumed the same meal with lower-linoleic-acid oils (HOSO and VOO in the chart below). The latter group had increased levels of the satiety hormone OEA, which is derived from monounsaturated fat and has the opposite effect of 2-AG and AEA [*,*].

The Role of CB1 Receptor in Obesity

The discovery of the endocannabinoid system and its relationship to weight management was a major breakthrough in obesity research. As we’ve discussed, the CB1 receptor, which is activated by endocannabinoids like 2-AG and AEA, is considered a key player in regulating appetite and energy balance.

In the early 2000s, a drug called Rimonabant was introduced as a promising weight loss treatment [*,*]. Rimonabant worked by blocking the CB1 receptors, which appeared to regulate appetite and lead to weight loss [*].

Patients using Rimonabant reported less hunger, and their appetite regulation and satiety signals seemed to be functioning properly. This allowed individuals taking the drug to consume food without restrictions and still avoid gaining weight or becoming obese [*].

But intentionally blocking CB1 receptors had unintended consequences, leading to an increased risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in some patients [*]. So, despite its effectiveness in promoting weight loss, Rimonabant was withdrawn from the market due to serious side effects [*]. Still, its ability to block CB1 receptors and effectively promote weight loss has informed our understanding of the endocannabinoid system's role in obesity.

Research has also found that mice that are genetically engineered to have their CB1 receptors blocked do not become obese, or at least not nearly as obese [*,*].

Bariatric surgery, an effective but extreme fat-loss intervention, also blocks CB1 [*]. The most common type of bariatric surgery is gastric bypass, where food is forced to bypass the stomach. This procedure is typically a last resort for morbidly obese patients who cannot lose weight through other means.

While the surgery carries risks, its success rate is impressive. One study reported that 85% of patients lose 50% of their excess body weight, and other studies have found that patients can maintain a 47-57% loss of excess weight for 5 to 7 years after surgery [*,*,*].

Although we know gastric bypass surgery works and is accompanied by reduced food intake and increased energy expenditure, researchers at the University of Washington recently demonstrated that gastric bypass works, in part, by lowering CB1 activation in the gut [*].

The researchers also found that the effects of gastric bypass surgery could be mimicked by administering Rimonabant, demonstrating that the two interventions share similar mechanisms — downregulating or blocking CB1.

Other research has shown that directly administering AEA can counteract the fat loss and metabolic improvements seen with gastric bypass surgery [*]. This is a noteworthy finding, as consuming more linoleic acid elevates AEA levels and can stimulate hunger. These results highlight the importance of both CB1 and AEA in the development of obesity.

Unfortunately, like Rimonabant, gastric bypass surgery can have serious adverse side effects [*,*,*].

Overall, CB1 receptors play a crucial role in weight management, with endocannabinoids like 2-AG and AEA stimulating appetite and contributing to weight gain. While interventions like Rimonabant and gastric bypass surgery have demonstrated the effectiveness of blocking or downregulating CB1 to aid with weight loss, they also come with severe unrelated side effects.

Nonetheless, these interventions have informed our understanding of the role that endocannabinoids play in obesity and highlight the need to limit your intake of seed oils, which are high in linoleic acid and can contribute to increased levels of AEA and 2-AG.

The Takeaway

Once consumed, linoleic acid is eventually converted to various metabolites in the body, including the metabolites of arachidonic acid such as 2-AG and AEA. This conversion process adds a layer to our understanding of how this fatty acid, found primarily in seed oils, can cause overeating and unwanted weight gain.

In addition to its role in obesity, other research has explored how the oxidation of linoleic acid can lead to the formation of harmful compounds that may contribute to chronic health issues.

When oxidized, linoleic acid can be converted into highly reactive and physiologically toxic unsaturated aldehydes, including 4,5-epoxy-2-alkenals, 2,4-alkadienals, 4-peroxy-2-alkenals, and 4-hydroxy-alkenals, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA) [*,*,*,*].

These compounds have been implicated in various pathological processes and further highlight the potential risks associated with high linoleic acid consumption [*,*,*].

Considering these findings, reducing linoleic acid intake by avoiding the consumption of seed oils and most packaged or fried foods that contain them may be an effective strategy for managing appetite, weight, and overall health.

Further research is needed to fully understand the complex interplay between dietary fats, endocannabinoids, and obesity. Yet, current evidence reinforces the importance of paying attention to the types of fats you consume — particularly avoiding seed oils.

Are Seed Oils Toxic? The Latest Research Suggests Yes

Seed oils never underwent safety testing for premarket approval. Here, we examine the disturbing toxicity and safety data that have come to light recently.

Why Are Fried Foods Bad for You? (The Real Reason)

Restaurants reuse cooking oil hundreds of times, creating harmful compounds like acrylamides, toxic aldehydes, hydroxylinoleate, free radicals, and trans fats.

Vegetable Oils: A History of Fats Gone Wrong

Vegetable oils like canola and soybean oil seem to be in everything. But it wasn’t always like this. Read the little-known history of vegetable oils here.