WRITTEN BY: Daniel J. Patterson

Article at a Glance

By the mid-1800s, industrial methods of mass production shifted the world towards cheap, unfamiliar sources of fats and oils.

As margarine and vegetable oils became increasingly popular, their purported health benefits were aggressively marketed despite being based on little scientific evidence.

Producers sought innovative ways to reduce the cost of producing goods, leading to the invention of Crisco, a solid fat made from cottonseed oil.

The success of Crisco opened up the widespread production of other vegetable oils, marketed as healthy despite little understanding of their health impact.

Palm oil was used as an alternative to partially hydrogenated vegetable oils due to its lack of trans fats but its widespread production has led to environmental destruction and threatened many endangered species.

The most prevalent vegetable oil in the U.S is soybean oil, which gained popularity in the mid-1900s, and is linked to both health and environmental issues.

The future of fat and oils lies in the ancient art of fermentation, which allows for the production of healthier fats that are more sustainable than oils derived from oil crop agriculture.

Introduction

Fried chicken, french fries, fried eggs, fried onions, deep-fried pizza, and yes, even deep-fried soda. Today, we live in a world of fried foods, nearly all of which are fried in vegetable oil.

But vegetable oils weren’t always in widespread use, and fried foods are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to foods made with vegetable oils.

Vegetable oils, often called seed oils, are now the most consumed food in the world after rice and wheat and make up 20% of our daily calories [*,*]. What most people don’t know, however, is that they can have a negative impact on human health and the environment.

From your favorite packaged foods to Michelin-starred restaurants to meal replacement shakes and even baby formula, vegetable oils are everywhere. Chips, cookies, popcorn, and coffee creamers all contain vegetable oils, as do unsuspecting foods that are marketed as healthy, like protein bars and salad dressings.

Aside from their use in food, vegetable oils are found in an assortment of products like cosmetics, soap, perfumes, candles, wood treatment products, and numerous personal care products [*]. In fact, vegetable oils (including olive oil) initially weren't even considered food.

Today, cultures around the world rely on vegetable oils as a main fat source. But this wasn’t always the case. And it’s no coincidence that chronic disease is increasing alongside the rise in seed oil consumption. Nowadays, at least 6 in 10 Americans suffer from chronic illness — a 700% increase since the first survey on the topic in 1935 [*,*].

In this article, we’ll cover the series of events that left our food system dependent on vegetable oils to the detriment of our health and our planet. We’ll also explore a viable solution — the path to a healthier world less reliant on destructive vegetable oils.

The Origins of Industrial Oils

Before vegetable oils were considered a food, let alone one of the most consumed foods in the world, the whaling industry played a critical role in supplying oils on a global scale. As the New York Times puts it:

“From the 1700s through the mid-1800s, oil extracted from the blubber of whales and boiled in giant pots gave light to America and much of the Western world[...] Whaling was the fifth-largest industry in the United States; in 1853 alone, 8,000 whales were slaughtered for whale oil shipped to light lamps around the world, plus sundry other parts used in hoop skirts, perfume, lubricants and candles.” [*]

Whale oil wasn’t used to feed the world; rather it was used to light it up, along with many other industrial applications. Interestingly, American sailors often indulged in large batches of doughnuts fried in whale oil [*].

By the mid-1800s, whale oil had fallen out of favor due to both declining whale populations and the rise of cheaper, innovative sources of lamp fuel like camphine and kerosene [*].

During this era, a surge of innovation shifted industries towards cheaper sources of energy like coal, electricity, and petroleum that could power factories and steam engines as well as heat and light people’s homes.

Industrial methods of mass production began transforming every aspect of our lives, from the clothes we wore to the foods we ate to the way we traveled. Instead of handmade goods, machines took center stage.

Machines, however, require lubrication, and oils and fats were commonly used as machine lubricants (among many other applications). Whale oil may have been out of the picture, but the demand for cheap sources of oil was only growing.

The mass production of consumer goods was also taking flight during this era, many of which, such as candles and soap, contained fats and oils.

Traditionally, soap and candles were made with lard and other animal fats, but producers were suddenly under pressure to embrace other sources of fat, or to stop making candles entirely, for at least three reasons:

Electricity and other sources of energy were set to largely replace candles.

Animal fats were a relatively expensive input.

The purity and cleanliness of animal fats were under scrutiny from the public and prominent journalist Upton Sinclair, known for exposing the appalling conditions of the meatpacking industry in the early 1900s [*].

As a result, producers sought innovative ways to replace animal fats and reduce the costs of producing various goods.

The Origins of Industrial Edible Oils

By the late 1800s, thanks to the invention of the cotton gin, cotton production was booming, despite one major nuisance to producers. Cotton production resulted in the buildup of unusable, toxic waste from cotton seeds [*].

Although oil could be extracted from these seeds for various uses, the unrefined oil was acutely (immediately) toxic to both humans and animals when ingested.

When candle-maker William Procter partnered with his brother-in-law and soap-maker James Gamble, they seized the opportunity to reduce the cost of soap and candle production by using cottonseed oil in their products [*].

With the help of new technology, the duo was eventually able to transform (or partially hydrogenate) liquid cottonseed oil into a solid fat that was creamy and butter-like.

In reference to cottonseed oil, the magazine Popular Science wrote: “What was garbage in 1860 was fertilizer in 1870, cattle feed in 1880, and table food and many things else in 1890” [*].

The butter-like byproduct of the cotton industry would soon become an everyday food in America.

Procter and Gamble called it Crisco, which was introduced to the public in 1911.

The Washington Times, November 7th, 1911 [*].

Due to advancements in the refinement process, cottonseed oil was no longer immediately toxic. However, the consumption of cottonseed oil and other vegetable oils appears to have chronic effects on our health, which would not be studied for decades to come, largely because chronic health issues were still relatively rare and not well-understood.

A Quick Note On Adulteration

Even before Crisco was introduced to the public, cottonseed oil was used to dilute more expensive oils and fats, like olive oil and lard. Due to its light flavor and color, cottonseed oil was largely undetectable as an addition to these products.

The adulteration of olive oil and lard allowed producers to lower their costs and extend the supply of their products. Discreetly cutting harder fats, like tallow, with cheap cottonseed oil also allowed producers to customize a product’s texture [*].

To this day, cheaper vegetable oils, like soybean oil, are often used to adulterate and lower the cost of extra virgin olive oils and avocado oils [*,*].

The Rise of Corn Oil, Soybean Oil, and Other Seed Oils

The success of Crisco opened up the floodgates for the widespread production of other cheap oils like soybean oil, corn oil, safflower oil, sunflower oil, and peanut oil. All the while, there was very little regulation surrounding their health claims.

Many of these oils are extracted from the seeds of crops, and yet they became known as “vegetable” oils or shortenings. The term “vegetable” oil certainly sounded healthier than “cottonseed” or “soybean” oil, but these oils weren’t exactly derived from vegetables like broccoli or carrots!

Clever marketing campaigns promoted vegetable oils and shortening as healthy and pure, and offered free cookbooks and free samples to consumers.

All of this resulted in the rapid (and global) rise of vegetable oil production throughout the 20th century. For example, in the United States alone, soybean oil consumption increased over 1,000-fold between 1909 and 1999 [*].

The rapidly rising consumption of vegetable oils meant that humans began consuming abnormally high levels of fatty acids that were entirely foreign to the human diet (like artificial trans fats), or consumed in minimal amounts throughout 99.9% of evolution (like omega-6 linoleic acid — a polyunsaturated fatty acid or PUFA) [*,*,*].

The “Heart Healthy” Era

In the eyes of the public, vegetable oils were gaining popularity and viewed as healthy, despite an increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, like heart disease, throughout the early 1900s.

Of course, correlation does not equal causation, but if the consumption of a food is increasing in line with increasing rates of chronic disease, it warrants further consideration.

With heart disease steadily on the rise, researchers all over the world began speculating on what was to blame. Many researchers concluded that heart disease was caused by smoking and brought on by other health issues like obesity and diabetes.

Other researchers pointed the finger more closely at our diets, noting the low incidence of heart disease in cultures eating traditional, pre-industrial diets [*,*].

One of the most well-known hypotheses for the uptick in heart disease was that saturated fats and cholesterol were to blame and that replacing them with vegetable oils would be healthier.

Vegetable oils generally contain low levels of saturated fat and were proven to lower serum cholesterol levels in clinical trials. However, lower serum cholesterol levels did not translate to fewer heart attacks, longer life, or better health [*,*,*].

Before any human trials had been conducted, leading health organizations began recommending vegetable oils as a possible means of preventing heart disease and reducing the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

These recommendations had a massive influence on the way that our nation thought about fats, and the food industry stood to benefit. Products that were formulated with vegetable oils and lower amounts of saturated fat could be marketed as heart-healthy.

After suffering a heart attack at age 64, even President Eisenhower adopted recommendations to consume less fat and replace the fat he was consuming with vegetable oils under the direction of his doctors. For the first time in history, Americans were tuning into real-time updates on a president’s health condition — twice per day press conferences for weeks.

The president’s diet was generally low in fat, but when he did eat fat, he relied on soybean oil, corn oil, and margarine. Though President Eisenhower’s health continued to decline, his doctor’s dietary recommendations would help shape the way the world dealt with heart disease and other chronic diseases for the coming decades.

Vegetable oil consumption would continue on its upward trajectory, with soybean oil taking the lead in the 1940s and 1950s, surpassing the use of cottonseed oil, butter, and lard [*].

Thanks to advances in processing and hydrogenation, the characteristics of soybean oil could be customized to meet the needs of producers. As a result, soybean oil was popularized and highly marketable for a number of different food applications.

The Artificial Trans Fats Saga

By the 1950s, vegetable oil manufacturers had mastered the process of partial hydrogenation, allowing products like Crisco and Kream Krisp to be even softer and easier to use, especially for frying.

Partially hydrogenated vegetable oils were seen as an appropriate alternative to solid fats like butter and coconut oil, which were high in saturated fat. Unfortunately, the process of partial hydrogenation poses a major health concern — it creates artificial trans fats.

The term artificial trans fats may ring a bell. In fact, you may have heard about the dangers of trans fat or that the outright addition of trans fats to food was finally banned in 2018.

Researchers had expressed concerns about the dangers of trans fats as far back as 1944 [*]. However, it wasn't until scientist Fred Kummerow started a legal battle against the FDA in 2013 that a ban began to take shape [*].

Kummerov warned the public about the harms of trans fats in 1957, but an entire industry had been built around partially hydrogenated vegetable oils and there wasn’t a viable alternative that was also low in saturated fat.

In response to a combination of factors, including increasing consumer concerns, public health recommendations, and the desirable texture of the fats, prominent restaurant chains like McDonald's, Burger King, and Wendy's decided to stop frying with beef fat or coconut oil in the early 1990s. Instead, they transitioned to using partially hydrogenated vegetable oils.

The food industry had already learned that oils and fats were a feature of products that could be changed. Though reluctant at times, companies were willing to change their inputs in light of new information or public pressure.

The fear of saturated fat meant that restaurants, food manufacturers, and consumers all relied on trans-fat-laden shortenings in their recipes. Their stability, low price, and neutral taste, also meant that there wasn’t a good replacement.

So, for decades before the 2018 ban, artificial trans fats were widely consumed, promoted as healthy, and intentionally added to foods. Unlike the natural trans fats in dairy, which have been linked to health benefits, artificial trans fatty acids are associated with a 23% to 26% increased risk of heart disease [*].

If the dangers of trans fats had been publicized, tens of thousands of products would have needed reformulation. So, the food industry was reluctant to change and even funded studies to create conflicting evidence showing that trans fats were harmless [*].

A food industry trade group even hired scientists to follow trans-fat researchers at conferences and object to conclusions made at the end of their lectures [*,*].

The efforts of the food industry prevailed. By the 1990s, there was overwhelming evidence demonstrating the harms of trans fat, yet they remained in widespread use for another two decades [*]. At its peak, the widespread use of artificial trans fats is estimated to have caused around 50,000 premature deaths per year in the United States [*].

Throughout the 1990s, a number of prominent studies were published demonstrating the harms of trans fats. One study, the Nurses’ Health Study, found that for every 2% increase in calories from trans fats, the risk of heart disease nearly doubles [*].

Ironically, an industry-funded study expected to exonerate trans fats ended up confirming that trans fats increased risk factors for heart disease [*]. This study, combined with the persistent efforts of researchers like Kummerow, eventually forced the food industry to change its position, leading to the eventual ban on artificial trans fats.

Today, there is no level of trans fat consumption that is considered safe. Regrettably, the first generation of partially hydrogenated shortenings like Crisco, Kream Krisp, and others, had a trans fat content as high as 50% [*,*].

Despite the fact that artificial trans fats were banned in 2018, vegetable oils are one of the few foods that still contain trans fats due to labeling loopholes. Vegetable oils, like canola oil, contain up to 3.6% trans fat, but since this falls below 0.5 grams per 14-gram serving, the trans fat content can be listed as 0 grams [*].

The Olestra Controversy

In the 1990s, during the height of the low-fat craze, another artificial fat substitute called Olestra was introduced to the public, backed by over 30 years and $500 million worth of research and development [*]. Olestra, which was developed by Procter & Gamble, the same makers of the original Crisco, provided the mouthfeel and taste of fat in foods and was designed to help people reduce their intake of saturated fat, cholesterol, and total calories.

Olestra, a synthetic fat molecule, was too large for the body to absorb and instead passed through the metabolism without adding any calories. It was incorporated into snacks like chips and pretzels that could for the first time boast a lower fat and calorie content.

Before long, the FDA received upwards of 20,000 complaints about Olestra’s effects, more than all food additives in history combined [*]. Olestra appeared to cause loose stools, cramping, malabsorption of several vitamins, and other health issues [*].

After a short stint, Olestra was abandoned by the food industry and subject to regulations, such as warning labels regarding Olestra’s effects on digestion.

Alternatives to Partially Hydrogenated Vegetable Oils

The food industry wasn’t oblivious to the problems with trans fat and the growing sentiment that trans fats posed serious health concerns. As of 2005, 18% of consumers were already aware that trans fats posed major nutritional problems [*]. Once again, the food industry needed an alternative. This time, the industry needed to replace partially hydrogenated oils at scale. In fact, the food industry wanted to get ahead of the problem and poured hundreds of millions of dollars into researching and developing solutions [*].

Of course, there was no drop-in replacement for partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, which were extremely customizable, lending themselves to a variety of uses from high-temperature frying to laminating pastries. Many of the replacements, particularly in bakeries and restaurants, involved blends of different oils and ingredients. At first, palm oil, which offered many of the culinary benefits of partially hydrogenated oils, seemed like the natural choice.

Palm Oil

Like partially hydrogenated oils, palm oil is cheap, semi-solid at room temperature, and can be used for a variety of purposes. Palm oil does not need to be hydrogenated and therefore contains no trans fats.

Historically, manufacturers avoided palm oil due to concerns over its higher saturated fat content [*]. But when trans fats were under the public microscope, palm oil’s lack of trans fats became more important than its levels of saturated fat.

While palm oil didn’t pose the same health concerns as partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, it caused an entirely different and devastating threat: environmental destruction.

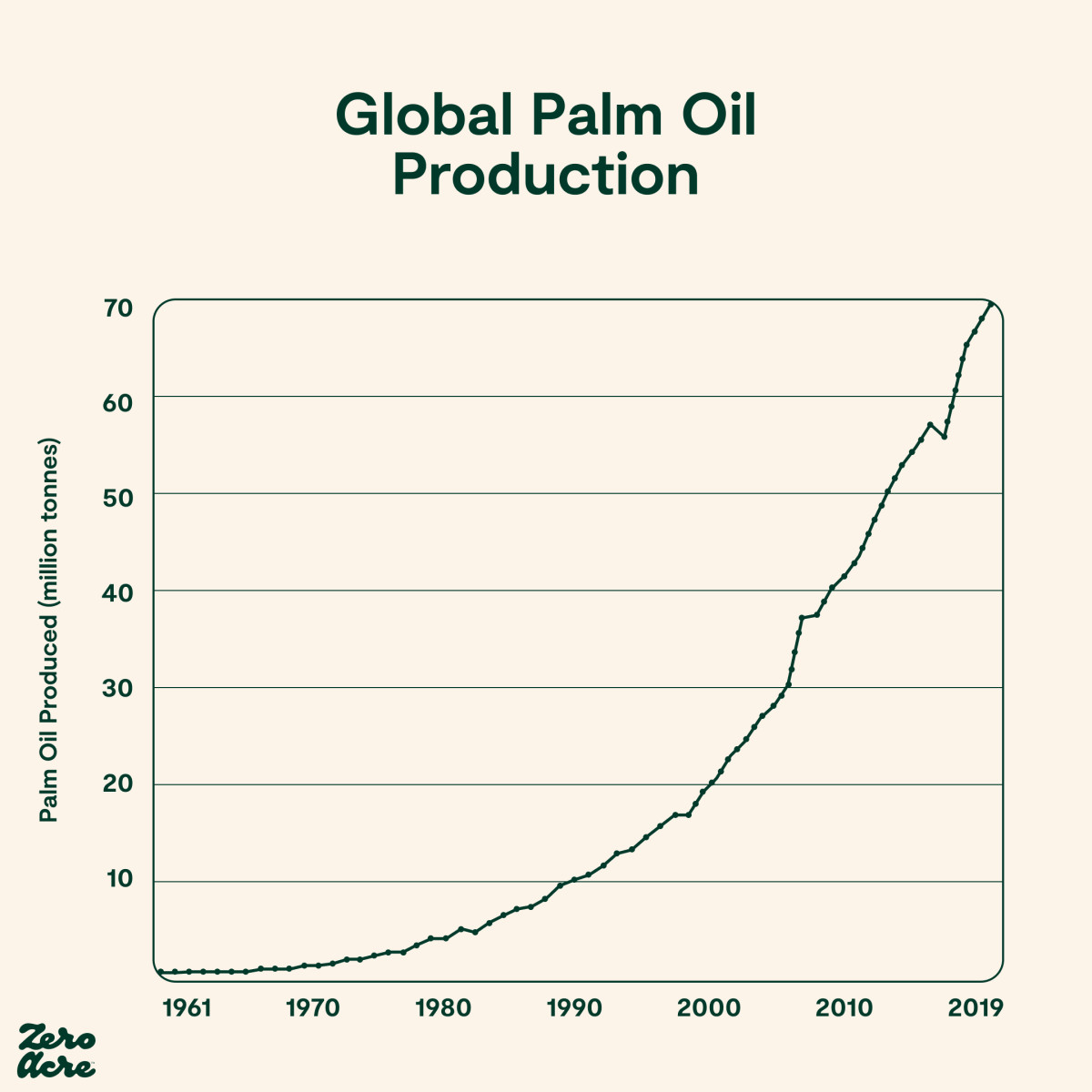

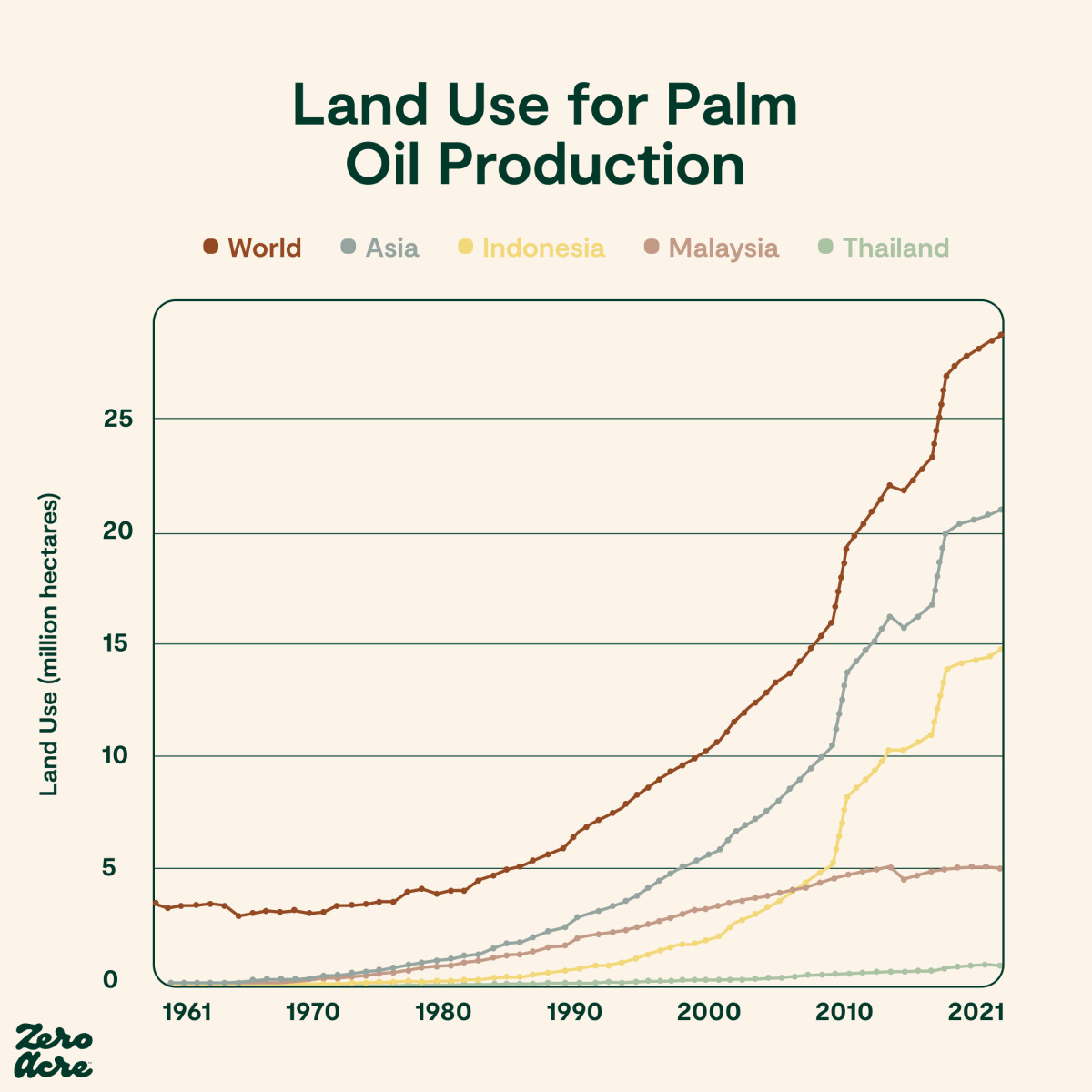

Palm oil only grows in tropical climates near the equator, and because of where it grows, vast swathes of rainforests are torn down to make room for palm oil agriculture. In fact, palm oil is one of the top three drivers of global deforestation [*].

Tropical rainforests are the most biodiverse regions on the planet, representing only 2% of the earth’s surface area, yet housing more than 50% of our animal and plant species [*].

Deforestation in the tropics isn’t just tearing down trees — it’s also driving carbon emissions and destroying the habitat of already endangered species like the orangutan, the Sumatran rhino, and the pygmy elephant. In fact, palm oil production threatens 321 species globally — more than any other oil crop [*].

Throughout the early 2000s, the expansion of palm oil plantations accelerated. Even though palm oil is the most efficient oil crop in terms of its yield, improvements in yield could not keep up with the global demand [*]. At its peak, palm oil expansion accounted for 40% of the deforestation in Indonesia [*].

Today, palm oil can still be found in about 50% of the products that line the shelves of U.S. supermarkets [*]. Its use is not limited to food products, however. Cosmetics, detergents, shampoos, and conditioners, often contain some form of palm oil.

As palm oil became notorious for its role in global deforestation, large corporations that used it faced backlash from consumers and government bodies. Palm oil production was also exposed for its child labor practices [*].

Policymakers around the world crafted legislation to curb the issues associated with palm oil. Non-profit organizations also sprung into action to enforce sustainable palm oil production and grant certifications to palm oil that met sustainable and fair trade criteria [*].

But it was too late. The backlash against palm oil shook the food industry. Its rampant use could no longer be justified in the eyes of the public. But a boycott on palm oil would prove to be even worse for the environment [*,*].

To reduce its reliance on palm oil, the food industry turned to other vegetable oils, like soybean oil, which posed concerns for both our planet and our health.

Soybean Oil

The most prevalent vegetable oil, by far, in the United States, is soybean oil, which experienced a meteoric rise in consumption since the 1950s. In 2019, soybean oil accounted for 14% of Americans’ calories [*].

Given its prevalence, it may be tempting to think that soybean oil is healthy or sustainable. But soybean oil is not a health food and it’s also problematic for the environment.

Researcher H.J. Dutton of the United States Department of Agriculture summarized the history of soybean oil, writing [*]:

“In the early 1940s, soybean oil was considered neither a good industrial paint oil nor a good edible oil. The history of soybean oil is a story of progress from a minor, little-known, problem oil to a major source of edible oil proudly labeled on premium products in the 1980s.”

For thousands of years, traditionally prepared soybeans played an important role in the human diet, in the form of fermented foods like tofu, tempeh, and soy sauce [*,*]. But up until the 20th century, soybean oil wasn’t used for cooking or consumed by humans in any meaningful quantity; World War I changed that.

With food shortages and increased demand for plastics, lubricants, fuel, and other products, producers began crushing soybeans, primarily for its oil. Later on, soybeans were crushed for the starchy soybean meal which was sold to meat and dairy farmers to supplement their animals’ diets [*].

The arrival of modern industrial processing allowed manufacturers to extract minuscule amounts of oil out of soybeans. Since this oil was fairly neutral and low in saturated fat, it was marketable for the food industry. It was also cheap and functioned well in a variety of food applications since it didn’t impart any particularly strong flavors.

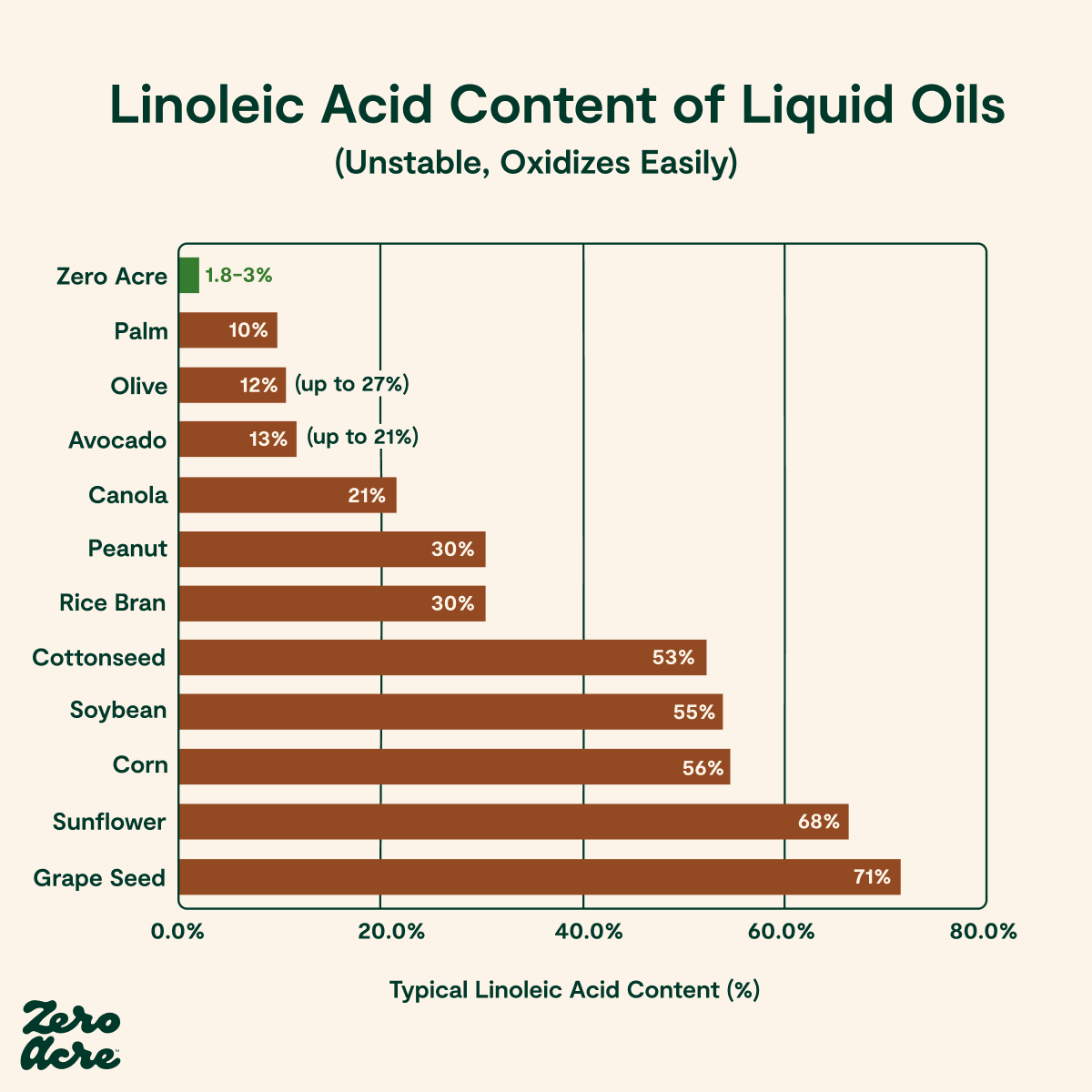

Unbeknownst to most consumers, soybean oil contains high levels of an unstable, reactive omega-6 fat called linoleic acid. While most whole foods contain evolutionary appropriate levels of linoleic acid, between 1-3%, common vegetable oils like soybean oil contain well over 50% linoleic acid [*,*].

As a direct result of increased vegetable oil consumption, the average American today consumes unprecedented levels of linoleic acid [*]. For the food industry, linoleic acid has always been a problem because of how easily it oxidizes or goes rancid, altering the flavor and nutritional profile of the food.

Due to their high linoleic acid content, vegetable oils easily oxidize when exposed to light and air, and even more so when exposed to heat. The instability of these oils poses a major challenge for manufacturers during the processing, storage, and transportation of vegetable oils.

Worse, vegetable oils break down into harmful compounds during cooking or frying, and in our bodies after we eat them. A 2015 paper found that foods fried in vegetable oils contain 100-200 times more toxic aldehydes than the safe daily limit set by the WHO [*].

When humans consume high linoleic oils, like soybean oil, the linoleic acid accumulates in our tissues or fat cells [*]. Excess linoleic acid intake has been linked to health issues like inflammation, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, neurological disorders, and even migraines [*,*,*,*].

The world’s growing consumption of soybean oil has also come at the expense of carbon-sequestering and biodiverse wilderness in South America, the United States, and Asia. Along with palm oil, soybean oil is also one of the top three drivers of global deforestation [*].

Public outcry over soy production’s role in deforestation garnered support for large corporations to sign a Soy Moratorium in 2006. This zero-deforestation agreement aimed to curb the clearing of the Amazon rainforest for soy production by banning the purchase of soy that was grown on deforested land [*].

Still, soybean oil is popular because it is cheap and convenient for producers. Without soybean oil, there would not be such a readily available source of starchy meal for feedlot animals. A world without soybean oil and other seed oils may encourage a shift to more sustainable forms of regenerative agriculture.

Today, soybean oil doesn’t just pose a problem for our health and the environment; its reliance on a fragile system of monocrop agriculture poses a problem for the future of our food system.

In recent years, the price of soybean oil has dramatically increased as a result of geopolitical distress, volatile weather conditions, and its delicate supply chain [*]. These fluctuations in price make it an unstable and unreliable commodity, which only adds to the urgency for a shift towards more sustainable forms of agriculture.

If fluctuations in the prices and supply of soybean oil and palm oil continue, the food industry will have to adapt again. As expected, the food industry hasn’t concentrated all of its resources and efforts on one or two oils.

What’s Left? Other Problematic Vegetable Oils

Today, we’re left with many types of vegetable oils, all of which require a sacrifice or major compromise. In many cases, when palm oil and soybean oil didn’t suffice, the food industry turned to oils like safflower oil, sunflower oil, corn oil, grapeseed oil, and rice bran oil.

For example, to eliminate the trans fats in potato chips, major companies switched from partially hydrogenated oils to non-hydrogenated corn oil and sunflower oil [*]. Although these oils may not contain trans fats, they still contain high levels of linoleic acid.

In addition to the health concerns posed by high levels of linoleic acid, many cooking oils have an alarming environmental impact:

In Spain, olive oil production results in the death of 2.6 million birds every year [*]

Canola oil has proven to be devastating for bee populations [*]

Avocado oil is wreaking havoc on natural ecosystems in Mexico [*]

Per liter of oil produced, coconut oil threatens more species than any other oil crop [*]

Typically, the oils with a smaller environmental footprint are higher in linoleic acid and more problematic for health. While oils extracted from fruit crops (olives, avocados, coconuts, palm fruit) are lower in linoleic acid, they tend to have a massive impact on land use, water use, biodiversity, and greenhouse gas emissions.

For example, due to its hefty irrigation requirements, olive oil requires more water than any other food crop, except for almonds. Olive oil also requires more water than eggs, pork, beef, and milk, per kilogram of food product [*].

And even though tropical oils like palm oil and coconut oil are lower in linoleic acid compared to seed oils, they compete with land for biodiverse rainforests.

And the trade-offs don’t stop there.

The food industry, as well as consumers, equally care about the culinary performance of cooking oils. The taste, texture, smoke point, shelf-life, and whether or not an oil is liquid or solid are all important factors.

For over a century, the food industry has grappled with many of these variables and continues to pour money into improvements.

In a 2021 lecture for the American Oil Chemists' Society, prominent researcher Dr. Erik A. Decker concluded, “After over 150 years of research we still don’t have control of lipid oxidation in foods” [*].

Perhaps, after 150 years of research, we should replace the high linoleic seed oils that are so prevalent in everyday foods. Lowering the linoleic acid content of foods would mark a significant step towards making them less susceptible to rancidity, oxidation, and waste.

In recent decades, scientists have developed sunflower oil and other seed oils that are bred to be lower in linoleic acid [*]. Although these seed oils are less susceptible to oxidation, the sustainability of these oil crops remains a pressing concern.

Vegetable oils are the fastest-growing sub-sector of agriculture, and their production is expected to grow 30% over the next four years [*,*]. Devoting more cropland to vegetable oils may continue to come at the expense of forests, grasslands, and room for actual vegetable and fruit crops.

The Future of Cooking Oils and Fats

One important lesson we can learn from the rise of vegetable oils is that the food industry is willing to adapt when a problem arises. As one food industry insider told trans fat researcher David Schleifer, P.h.D [*]:

“If something becomes a problem then, you know, by the time it becomes a problem we need to have a solution and to do that we have to anticipate the problem and make those investments.”

The alarm bell on the massive problem of vegetable oils is ringing loud and clear.

At Zero Acre Farms, we believe that people shouldn’t have to make a compromise when choosing a cooking oil or fat.

Unlike vegetable oils, Zero Acre oil can be produced anywhere in the world. Since the process of fermentation is not dependent on location or climate, tropical rainforests no longer need to be torn down to make way for the production of cooking oils.

In other words, thanks to the art of fermentation, healthier oils and fats don’t require a trade-off. The production of Zero Acre oil results in zero deforestation.

Compared to soybean oil, Zero Acre oil requires 83% less water, emits 86% fewer greenhouse gases, and uses 90% less land. And unlike seed oils, it contains evolutionarily appropriate levels of 1.8-3% linoleic acid.

If Zero Acre oil was only healthier and more sustainable than vegetable oils, it wouldn’t be a viable replacement for vegetable oils at scale. That’s why we introduced an oil that also has better culinary performance – a higher smoke point, a neutral taste, and an ability to stay liquid at a variety of temperatures.

Zero Acre oil is a new type of cooking oil, but the fats it contains are nothing new. Unlike partially hydrogenated vegetable oils and Olestra, Zero Acre oil does not introduce any new compounds to the human diet — just the same heart-healthy monounsaturated fats that nature has provided us with for hundreds of thousands of years.

There are many ways in which we can improve the health of the world, but the shift towards healthier and more sustainable fats and oils is a crucial step. If our planet was being destroyed for some miraculously beneficial food, then perhaps our actions could be justified.

Instead, our planet is being destroyed to grow foods that make us sick. We hope to change that.

The World Needs an Oil Change

Zero Acre Farms is on a mission to remove destructive vegetable oils from the food system. Learn how vegetable oils are at the center of disease and environmental destruction, and how we plan to change that using the ancient art of fermentation.

Are Seed Oils Toxic? The Latest Research Suggests Yes

Seed oils never underwent safety testing for premarket approval. Here, we examine the disturbing toxicity and safety data that have come to light recently.

The Purpose and Plan Behind Zero Acre Oil

The launch of Zero Acre oil marks our first step toward displacing vegetable oils. There no longer needs to be a tradeoff between health, sustainability, and culinary performance.